Deconstructing Genderless Fashion.

As a heterosexual, married female I suppose that in many ways I embody a way of life deemed traditional by many of my liberal thinking colleagues. For that reason it is with caution that I share my views, or rather contemplations, on the subject of genderless fashion. As a gender binary individual, what could I possibly know, let alone understand, about genderless fashion?

Many see genderless fashion as the effort of marketing gurus to tap into a highly politicized conversation around gender in order to appeal to their liberal consumers. But what exactly is gender? Some use it when referring to a person’s sex. Incorrectly so, as sex refers primarily to the physical attributes of the human body and is generally (with some amount of exception) binary at birth. Gender, on the other hand, is much more complex: it denotes a person’s appearance, behavior, and role and is defined by culture as specific traits associated with one’s biological sex.

OUR SENSE OF GENDER IS A CONCEPT THAT GROWS ON US, OR PERHAPS, WE GROW INTO IT.

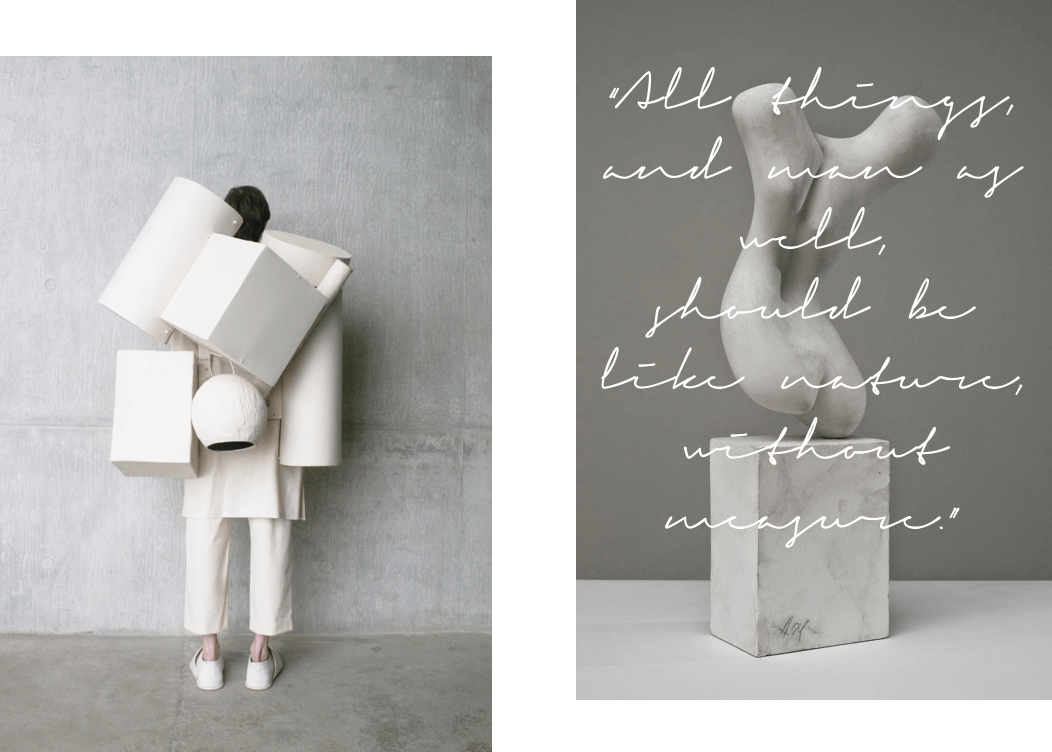

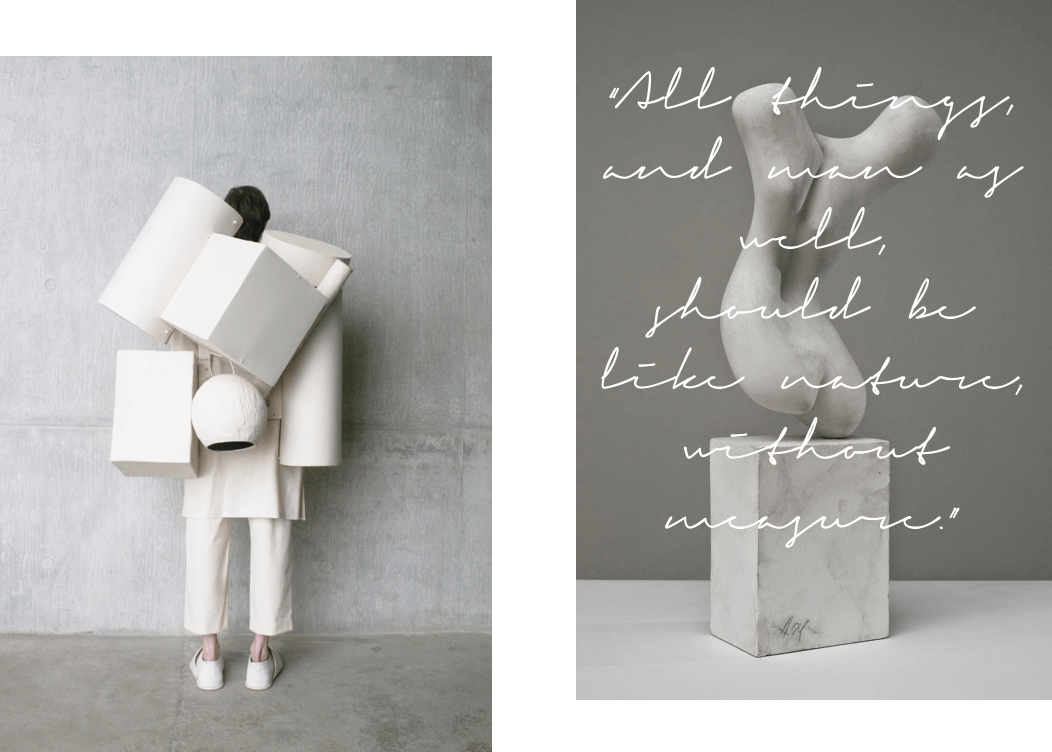

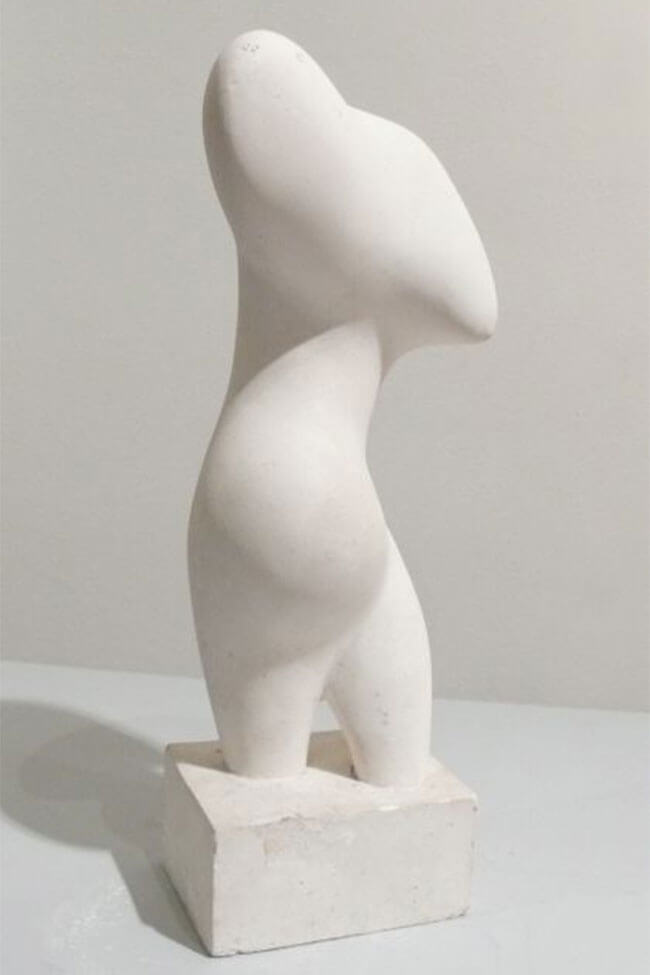

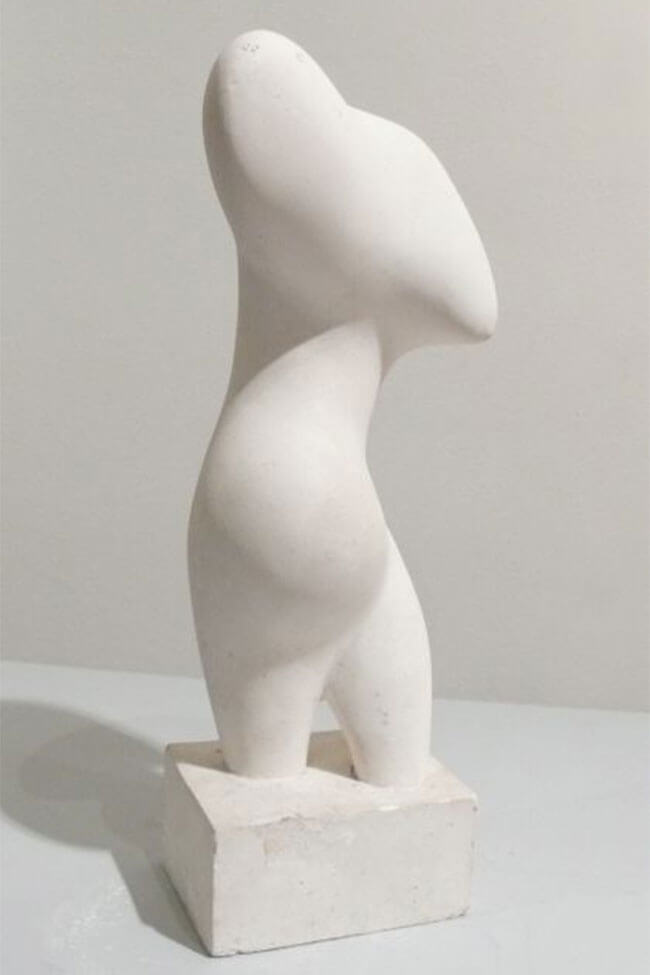

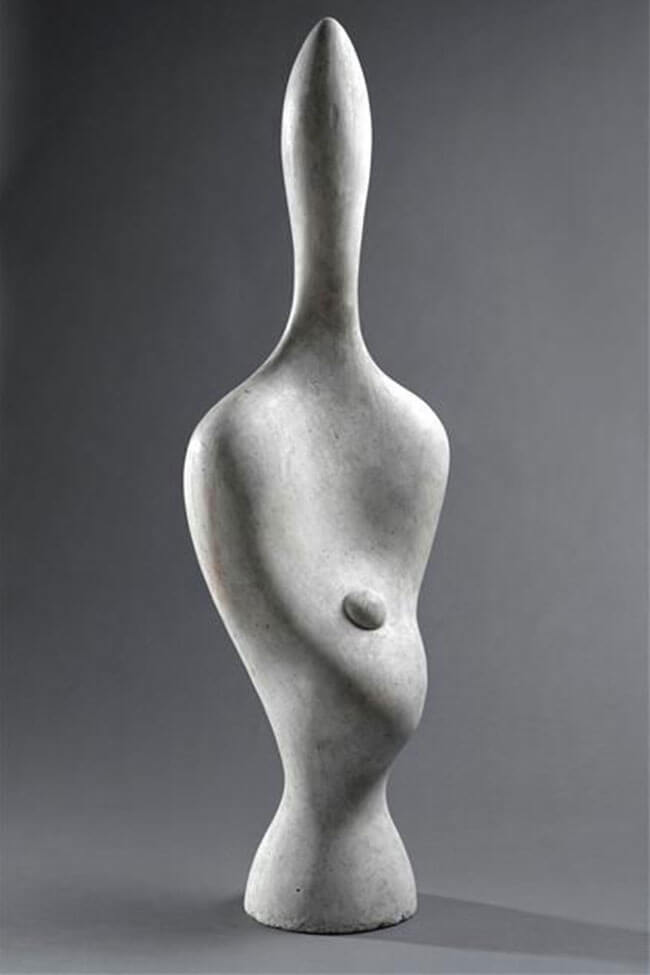

Body shape and clothing are intrinsically linked. (Image: sculpture by Jean Arp)

Gender identity, a person’s ability to label his or her own sex correctly and to identify other people as male or female, is developed by 2 years old. For most children, it can already be observed between 6 and 12 months. By the age of 4, questions such as “When I grow up, will I be a mommy or daddy?” will have given way for what is termed ‘gender stability’, the understanding that one’s gender is here to stay.

From a psychological perspective there is much discussion and little agreement as to how gender is developed. No doubt, social learning plays a big role in the formation of our gender understanding, as does reinforcement. As we observe behavior, symbolic meaning is incorporated into our understanding and interpretation of the world. It is our default to model the behavior of other humans that are most like us. When this behavior is then reinforced by, say, encouraging girls to play with dolls while boys play with trucks, our social cognition of gender is cemented. But it’s not that simple. Even in cases where gender reinforcement is absent, children can be observed to discriminate on the basis of sex, with same-sex playmate preferences being the norm. And there it is: the old debate between nature and nurture.

Clothing encompasses both – nature and nurture. Clothing primarily serves the needs of our physical bodies. It acts as a second skin that protects the body from the influences of the environment. Equally, however, it serves a cultural purpose. How we dress helps us define who we are (or who we choose to be) and how we see others. It communicates preferences and belonging and is an integral part of human interaction.

So where does fashion come in? The way I see it, fashion can be understood as a cultural institution within society. In this context, clothing has been used for centuries to define and establish gender. By observing culturally appropriate gender specific norms of dressing, individual understanding of gender is influenced, formed and subsequently expressed and perpetuated. Of course, the meaning of gender signifiers in clothing can evolve and change through appropriation. A woman wearing trousers prior to the 20th century was considered a crime. In extreme cases, wearing trousers could put a woman in jail, as in the case of Puerto Rican labor activist Luisa Capetillo in 1919, though just for a brief stint. Obviously, gender association with trousers have changed significantly since then. So could trousers be considered genderless clothing? Trousers for men and women are still constructed in significantly different ways, but according to Selfridges, that doesn’t stop consumers from purchasing those intended for the opposite sex.

DOES AN ITEM THAT WAS INTENDED FOR ONE SEX, WHEN WORN BY THE OTHER, BECOME GENDERLESS?

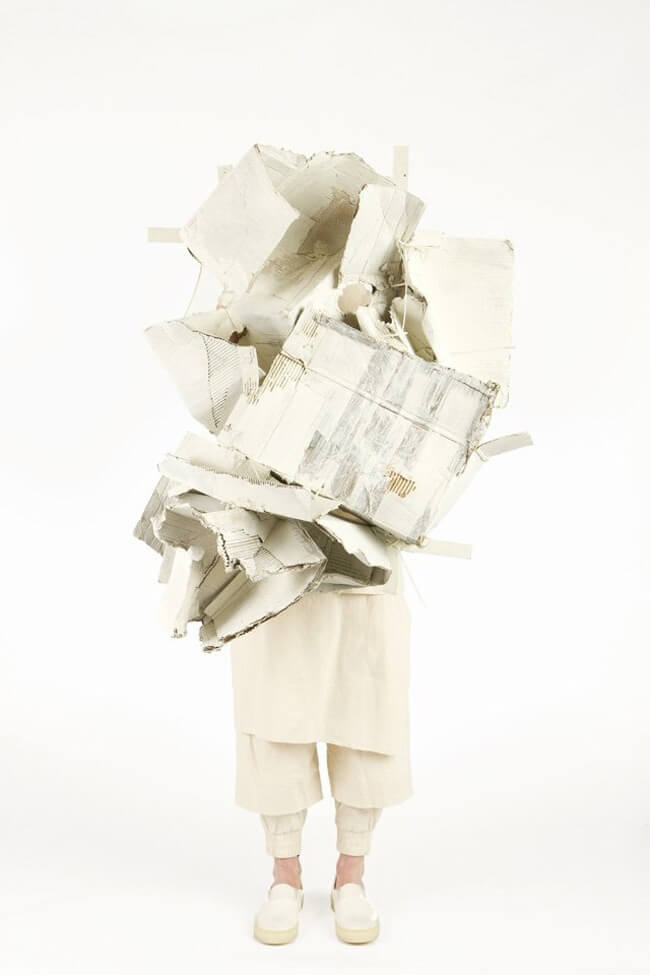

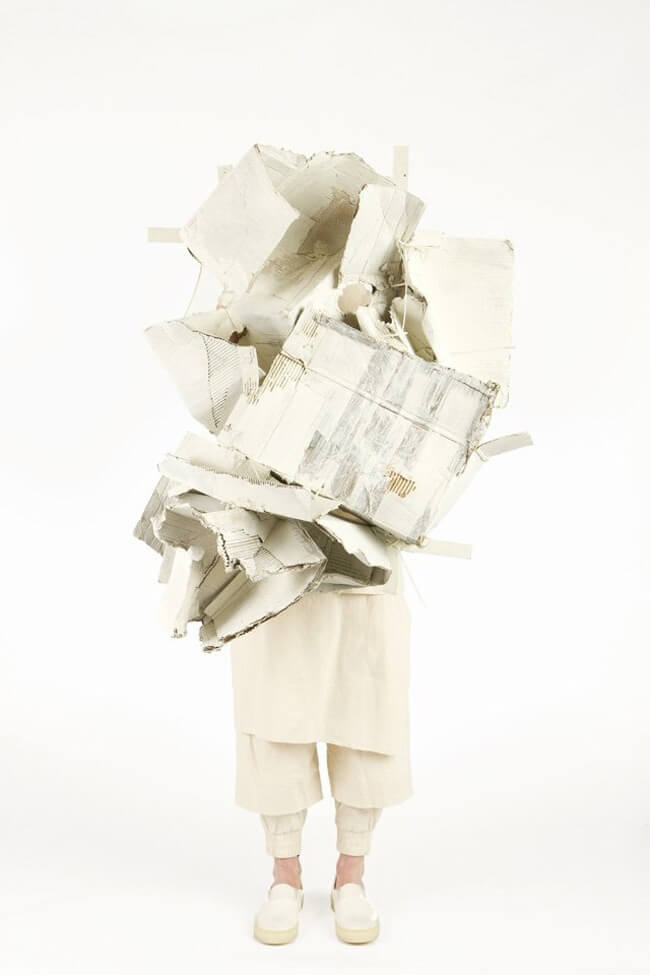

Gender - a cultural construction. (Image: Craig Green – AW 2013)

Clearly, genderless fashion is a concept that is hard to define. There are as many different interpretations of genderless clothing as there are words to describe it: “agender”, “androgynous”, “unisex”, to name but a few. Some contemporary designers use it to refer to clothes designed for male bodies exhibiting feminine signifiers such as frills or flower patterns. This way of dressing can be observed as far back as King Louis XIV of France and as recent as A.W. Anderson’s Spring Summer 2013 collection. Historically, however, frills were worn by men not as a signifier of gender but of class. There are similar examples of females being dressed in traditionally male silhouettes such as the suit and tie, take Marlene Dietrich in the 1930s, for example. But does the fact that a woman is wearing masculine clothing make the clothing genderless? Or is this rather, similarly to the frills, a way to use clothing to signify power and status – a political statement?

From a cultural perspective, defining “genderless fashion” is somewhat tricky. What is considered feminine dress in one (sub)culture may be a perfectly acceptable way of dressing for males in another, or vice versa. Perhaps, we come to the realization that clothes (I’m referring to the actual physical object) are in fact always genderless to begin with. It is rather our culture and its norms that ascribe a gender to an item of clothing and by continually labeling it as thus reinforce the way it is perceived. In the recent pop up shop “Agender”, which was build inside Selfridges, creative director Faye Toogood made it a point not to divide the space according to binary labels and used intentionally neutral packaging “to free [...] from preconceptions that would ordinarily colour such purchases” (Toogood, 2015). Could it be possible that merely omitting labels is enough to result in genderless clothing?

In my fashion school bubble, “genderless” is often used to refer to clothing of oversized silhouettes. I suppose this approach makes a lot of sense. Genderless clothing wouldn’t be genderless if it didn’t fit both the male and female physical frame. But then again, the oversized trend could also be a simple byproduct of a general trend towards more comfort in fashion and gender may well have very little to do with it. Nevertheless, it does highlight the importance that body shape plays in discussions of genderless clothing. While female bodies are distinctly different from male bodies, there are as many variations in proportion and size between females as there are between males. In some cases, proportion and size may be less distinct between sexes than when comparing within the same sex.

BUT THEN AGAIN, CAN A BRA EVER BE GENDERLESS?

Genderless fashion, it seems, would have to be clothing that is culturally and physically appropriate for both sexes within a certain time and place. The irony in this is that as society evolves, the meaning we ascribe to the clothes we wear will inevitably change. Historically there has never been a fixed category for genderless fashion. Is it a phenomenon significant of our time, one that is perhaps linked to a never before experienced freedom to express one’s gender however one likes? Does a sequin skirt worn by a man become genderless once a culture accepts men that choose to dress in this way? Can clothing ever cease to be used to construct and express our gender?

My high school required us to wear uniforms in our PE classes. The uniform consisted of a white cotton tshirt with the school’s name printed on the front, a pair of blue shorts and a grey hoody for the cold days. While sizes varied, boys and girls wore the same clothes. Of course, there are differences in sports uniforms for men and for women, especially at the more professional levels. Generally speaking, though, a plain white cotton tshirt and a hooded sweater are perhaps the only items of clothing that without a doubt can be considered genderless. In some circles, a white cotton tshirt is indeed a fashion statement, as is a hoody. For most people, however, these items are associated with functional wear; clothes to be worn in the comfort of the home or to keep warm on a quick trip to the night shop around the corner or to the gym on a chilly morning. To be considered genderless these items of clothing are confined to a very tight space. Depending on the culture in which they are worn, just a slight alteration to the cut, the pattern or the fabric, can deem them anything but genderless.

GENDERLESS FASHION, IT SEEMS, IS AS FLUID AS THE DEFINITION OF GENDER ITSELF; FOREVER RECONSTRUCTING ITS MEANING WITHIN TIME, SPACE AND CONTEXT.

If history can be trusted to repeat itself, then what is deemed genderless today, may be considered distinctly male or distinctly female tomorrow. It is as though nature always comes out on top and the pendulum finds its equilibrium right in the middle, in the conflict zone between male and female. When Gabrielle Chanel observed that physically restrictive clothing was keeping women from participating in work outside the home, she introduced an entirely new silhouette that liberated the women of her generation. Rather than trying to fit fashion within a static identity, be it masculine, feminine or genderless, perhaps we ought to see it as a tool. A tool that can be used to define and redefine the notion of gender, based on the needs of the society it caters to and in the way that is most relevant at the time. And perhaps, most importantly, it is in the interest of the development of our sense of self that these two extremes exist and that they find their expression in the signifiers attributed to our clothes. For without them, how would we be able to define for ourselves and communicate to others who we are and who we’re not, whatever that may be along the gender spectrum?

Images are not my own. Credit: Fashion by Craig Green (MA collection in title image, SS 2014 bottom right and left), Sculptures by Jean Arp